Screw Cut-out and Implant Failure in High BMI Patient Following TLIF: A Case Report and Technical Considerations

Case Report | Vol 2 | Issue 3 | September-December 2025 | page: 33-40 | Arvind Vatkar, Sachin Kale, Sumedha Shinde

Submitted Date: 02-07-2025, Review Date: 07-08-2025, Accepted Date: 05-10-2025 & Published Date: 10-12-2025

https://doi.org/10.13107/joc.2025.v02.i03.42

Authors: Arvind Vatkar [1], Sachin Kale [2], Sumedha Shinde [3]

[1] Department of Orthopaedics, MGM Medical College, Nerul, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.

[2] Department of Orthopaedics, D Y Patil School of Medicine and Hospital, Nerul, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.

[3] IHBT Department, Sir JJ hospital, Byculla, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Arvind Vatkar,

Department of Orthopaedics, MGM Medical College, Nerul, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.

E-mail: vatkararvind@gmail.com

Abstract

Background: Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) is a well-established surgical technique for the treatment of symptomatic lumbar spondylolisthesis. However, technical errors in pedicle screw placement, particularly in patients with elevated body mass index (BMI) and altered spinal anatomy, can result in implant failure and poor clinical outcomes.

Case Presentation: We present a 42-year-old obese female who developed symptomatic screw cut-out with implant failure two months following TLIF with posterior instrumentation for Grade III spondylolisthesis at L3-L4 and L4-L5. Initial postoperative recovery was favorable with resolution of preoperative radicular symptoms. However, the patient subsequently developed recurrent severe left lower limb radicular pain and low back pain with significant functional impairment and gait disturbance. Radiological investigation revealed malposition of pedicle screws with cut-out at L3 (bilaterally) and L4 (left side), with progressive loss of fusion correction.

Conclusion: This case emphasizes the critical importance of meticulous intraoperative screw placement technique, judicious use of imaging modalities (fluoroscopy, CT guidance, or navigation systems), and heightened vigilance in high BMI patients where anatomical landmarks are obscured and technical challenges are magnified. We discuss the mechanisms of screw cut-out, risk factors in obese patients, radiological recognition of implant failure, and management strategies.

Keywords: Screw cut-out, Implant failure, TLIF, High BMI, Complications, Revision surgery

Introduction

Lumbar spondylolisthesis is a common degenerative condition affecting the aging population, characterized by anterior slippage of one vertebral body on another. When conservative management fails, surgical stabilization with interbody fusion and posterior instrumentation is indicated [1]. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) has become increasingly popular due to its minimally invasive nature, preservation of posterior elements, and favorable fusion rates compared to traditional posterolateral approaches [2, 3].

Postoperative complications following TLIF remain a significant concern, with reported incidence rates varying from 5% to 30% depending on the definition and surveillance methodology used [4]. Among these complications, hardware failure—specifically pedicle screw cut-out—represents one of the most functionally disabling and technically challenging problems requiring revision surgery [5].

Pedicle screw malposition is recognized as an independent risk factor for implant failure, particularly in patients with poor bone quality, high mechanical loading (obesity), and inadequate surgical technique [6, 7]. Obese and overweight patients present unique technical challenges during spine surgery: their increased soft tissue thickness obscures anatomical landmarks, altered spinal biomechanics increase stress on implants, and osteopenia (commonly associated with obesity) compromises screw purchase in bone [8].

This case report describes the clinical presentation, radiological findings, and management considerations for a 42-year-old obese female who developed symptomatic screw cut-out following index TLIF. We discuss the mechanisms of failure in high BMI patients, review preventive strategies, and emphasize the importance of accurate screw placement technique and intraoperative imaging in this challenging population.

Case Presentation

Clinical History

A 42-year-old female presented to our clinic with a history of chronic low back pain (LBP) and left lower limb radicular pain of 18 months’ duration, initially managed conservatively with analgesics, physiotherapy, and epidural steroid injections without sustained relief.

Preoperative Assessment:

The patient reported progressive radicular pain radiating from the left lower back down to the lateral leg and foot, associated with neurogenic claudication limiting walking tolerance to approximately 50 meters. She described the pain as sharp and burning in character, with associated numbness in the lateral border of the left foot (L5 distribution). Nighttime symptoms frequently disrupted sleep, and pain was inadequately controlled despite high-dose nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Physical examination revealed:

– Body habitus: Obese (height 155 cm, weight 120 kg, BMI = 50.2 kg/m²)

– Lumbar range of motion: Markedly restricted, particularly forward flexion

– Neurological examination: Decreased strength in left ankle dorsiflexion (4/5), diminished sensation over lateral leg and dorsum of left foot, hyperreflexic left knee and ankle reflexes, positive left Lasègue test (straight leg raise limited to 30 degrees)

– Palpation: Significant tenderness over L4-L5 region with paraspinal muscle spasm

Imaging and Diagnostic Findings:

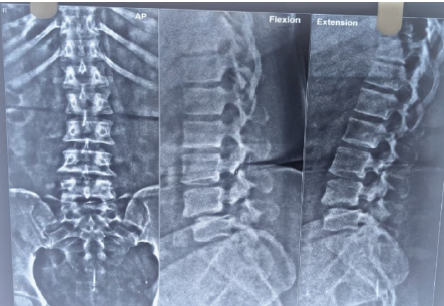

X-ray suggested-

– Grade III anterior spondylolisthesis of L4 on L5 with 50% slippage

– Grade II anterior spondylolisthesis of L3 on L4 (Figure 1)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine demonstrated:

– Grade III anterior spondylolisthesis of L4 on L5 with 50% slippage

– Grade II anterior spondylolisthesis of L3 on L4

– Severe stenosis at L4-L5 with marked compression of the thecal sac

– L4-L5 disc prolapse with significant left lateral recess stenosis causing compression of the left L5 nerve root

– L3-L4 central stenosis with bilateral foraminal stenosis, more pronounced on the left

– Preserved intervertebral disc heights at treatment levels, with no evidence of significant discogenic degeneration

Surgical Procedure

Preoperative Planning:

Given the severity of symptoms refractory to conservative management, significant neurological deficit, and imaging confirmation of neural compression, the patient was counseled regarding surgical intervention. TLIF with posterior instrumentation from L3 to L5 was planned to address the stenosis, decompress the neural elements, restore intervertebral height and disc space, and stabilize the spondylolisthesis.

Operative Findings:

Under general anesthesia, a midline posterior approach was performed. Bilateral paraspinal muscle dissection and exposure of the L3-L4 and L4-L5 levels were accomplished. Laminectomy and foraminotomy provided adequate decompression of neural elements bilaterally.

Transforaminal interbody fusion was performed at both levels using expandable titanium interbody cages. Posterior instrumentation consisted of pedicle screws (6.5 mm diameter, 45 mm length) and rods placed bilaterally at L3, L4, and L5 levels. Intraoperative fluoroscopy was used for screw placement guidance; however, due to the patient’s obesity and soft tissue thickness, optimal screw trajectory confirmation was challenging.

Following instrumentation, the patient’s IONM signals remained stable throughout the procedure with no significant changes, and wound closure was performed in layers without complication. Estimated blood loss was 350 mL with a total operative time of 145 minutes.

Immediate Postoperative Course

The patient’s immediate postoperative period was unremarkable. Pain assessment at 24 hours postoperatively revealed significant improvement compared to preoperative levels. She was mobilized on postoperative day 2 with physiotherapy assistance and demonstrated good tolerance for walking with a lumbar support brace. At discharge on postoperative day 5, neurological examination showed resolution of the preoperative left lower limb radicular pain and weakness, with restoration of left ankle dorsiflexion strength to 5/5.

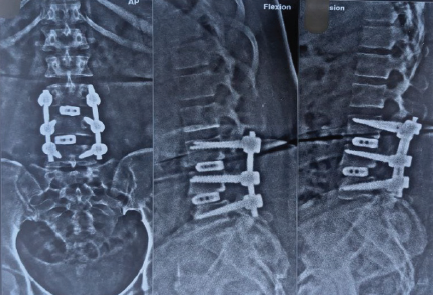

Postoperative plain radiographs (anteroposterior and lateral views) and CT imaging were obtained on postoperative day 2, which at that time appeared acceptable, though the quality was limited by streak artifact from metallic implants. In 1 week, x-ray was taken as shown in Figure 2.

Clinical Deterioration—Two Months Postoperatively

Presenting Symptoms:

Approximately 8 weeks after surgery, the patient returned to clinic with recurrent and progressively severe left lower limb radicular pain and low back pain.

She reported sudden worsening of symptoms beginning approximately 5 weeks postoperatively, coinciding with her initiation of regular activities. The character of pain was identical to her preoperative symptoms: sharp, burning radicular pain down the left leg with associated neurogenic claudication limiting ambulation to approximately 100 meters.

Additionally, she reported increasing low back pain with difficulty walking, prolonged standing, or sitting. The patient noted that pain was present at rest and worse with activity. She denied new-onset bowel or bladder symptoms, fever, or systemic illness.

Clinical Examination at 2 Months:

– General: Obese female, alert and oriented, in obvious discomfort

– Vital signs: Stable; no fever

– Lumbar examination: Marked tenderness over the L4-L5 surgical region; bilateral paraspinal muscle spasm; significant restriction of lumbar flexion and extension

– Neurological examination: Recurrent left L5 radiculopathy with decreased ankle dorsiflexion strength (4/5); positive left Lasègue test; diminished sensation in left L5 distribution

– Gait: Antalgic gait with splinting of lumbar movements

– No signs of infection (no wound drainage, erythema, or warmth)

Imaging at 2 Months Postoperatively

Plain Radiographs (AP and Lateral Views):

Anteroposterior radiograph demonstrated:

– Left-sided L4 pedicle screw clearly projecting outside the lateral border of the L4 vertebral body, consistent with screw cut-out

– Bilateral L3 pedicle screws malpositioned, with both screws demonstrating medial perforation through the vertebral body

– Progressive loss of fusion correction at L3-L4 with restoration of slip to approximately 30% (compared to preoperative 50% slip, representing improvement but still significant)

– Loss of intervertebral height at L4-L5 compared to immediate postoperative films

Lateral radiograph revealed:

– Sagittal malalignment with loss of lordotic correction at the fused levels

– The L4 left screw visualized in cross-table lateral view demonstrated substantial cranial migration out of the L4 pedicle with the screw tip lying within the spinal canal

– Evidence of hardware subsidence into the vertebral bodies

Magnetic Resonance Imaging:

MRI of the lumbar spine (T1 and T2-weighted sequences) demonstrated:

– Interval migration of pedicle screws with the left L4 screw now projecting into the spinal canal, impinging upon the traversing left L5 nerve root

– Subtle compression of the left L5 nerve root by the malpositioned screw at the L4 level, correlating with the patient’s L5 radiculopathy

– No new disc herniation at the fusion levels

– Satisfactory interbody cage positioning bilaterally at L3-L4 and L4-L5 with no subsidence into adjacent vertebral bodies

– Bilateral facet arthropathy at L3-L4 and L4-L5 unchanged from preoperative imaging

– No evidence of infection or abscess formation

– Fusion masses not yet well-developed (early postoperative period), as expected at 2 months

Computed Tomography Scan (Thin-slice, Multiplanar Reconstruction):

High-resolution CT imaging provided superior detail:

– Definitive confirmation of left L4 pedicle screw cut-out with lateral wall perforation and intra-canal migration

– Bilateral L3 screws with medial vertebral body penetration; right L3 screw mildly malpositioned but within acceptable limits; left L3 screw significantly medial with penetration into the vertebral body

– Vertebral bodies at L3, L4, and L5 demonstrated relatively preserved bone mineral density for the patient’s age (no significant osteopenia), but bone quality was not exceptional

– Screw tracks within the pedicles showed suboptimal trajectories, with both L3 and L4 screws positioned too medially from their insertion point

– No evidence of screw fracture or loosening at the implant-bone interface; failure was primarily due to malposition rather than metallurgical failure

Clinical Correlation and Diagnosis

The constellation of clinical findings—recurrent L5 radiculopathy, imaging evidence of screw cut-out and nerve root compression, temporal relationship to surgical intervention, and absence of alternative etiology (infection, discogenic pathology)—established the diagnosis of symptomatic pedicle screw cut-out with iatrogenic neural compression following index TLIF.

Discussion

Mechanisms of Pedicle Screw Failure

Pedicle screw failures are classified into several mechanisms: (1) screw loosening at the bone-implant interface, (2) screw breakage (rare with modern metallurgy), (3) screw cut-out through vertebral body, and (4) screw malposition with inadequate purchase or misalignment [5, 6]. In this case, the primary mechanism was malposition with subsequent cut-out, whereby screws placed in suboptimal trajectories (too medial) progressively migrated, eventually perforating vertebral cortices and entering the spinal canal.

Screw cut-out is thought to result from several factors acting in concert [5, 7].

1. Initial Malposition: Suboptimal screw placement predisposes to failure. Too-medial trajectories (as in this case) reduce purchase in cortical bone and increase stress concentration within the vertebral body.

2. Cyclic Loading and Micromotion: The spine is subject to repetitive loading with each movement. In the presence of malpositioned screws with inadequate initial purchase, cyclic micromotion at the bone-implant interface generates wear and progressive enlargement of the screw hole.

3. Bone Resorption and Osteoporosis: Screw holes represent stress risers in bone. In areas of poor bone quality or in the presence of stress shielding, bone resorption accelerates, widening screw tracks. Although this patient did not have radiological osteoporosis, obesity is associated with metabolic alterations affecting bone quality (lipotoxicity, insulin resistance, inflammation), which may compromise mechanical properties despite normal bone mineral density [8, 9].

4. High Mechanical Loading: Obesity significantly increases compressive and shear loads on the lumbar spine. A patient weighing 120 kg experiences substantially greater biomechanical stress compared to average-weight individuals. This elevated loading, particularly at the implant-bone interface, accelerates screw migration and cut-out [8].

5. Loss of Fusion: If solid fusion does not occur (which is still evolving at 8 weeks postoperatively), continued motion at the fusion site stresses the hardware, promoting screw migration. Early radiographs demonstrated beginning fusion incorporation, but this was incomplete and insufficient to protect malpositioned screws.

Risk Factors in High BMI Patients

Obese patients undergoing spine surgery face several compounded risks for implant failure: [8, 10]

Intraoperative Technical Challenges:

– Obscured anatomical landmarks due to increased soft tissue

– Deeper operative field with longer instruments, reducing precision

– Increased blood loss and operative time

– Difficulty in accurate fluoroscopic imaging due to body habitus

– Limited ability to palpate anatomical structures for confirmation

Biomechanical Factors:

– Significantly increased axial and shear loading on implants

– Altered spinal biomechanics with increased facet loading

– Increased intersegmental motion at the fusion level if arthrodesis is incomplete

Bone Quality Considerations:

– Obesity-related metabolic dysfunction affecting osteocyte function and bone microarchitecture despite normal bone mineral density (“fragile fat” phenotype)

– Impaired biological response to injury and delayed healing

– Increased systemic inflammation compromising bone-implant integration

In this specific case, the patient’s BMI of 50.2 kg/m² represented severe obesity with all the aforementioned risk factors present. The combination of difficult visualization intraoperatively, greater mechanical loading in the postoperative period, and potentially compromised bone quality created a “perfect storm” for implant failure when compounded with screw malposition.

Radiological Features of Screw Cut-out

Recognition of screw malposition on imaging is essential for early intervention [5, 11].

Plain Radiograph Findings:

– Lateral projection of pedicle screws on anteroposterior view (medial-to-lateral trajectory error)

– Cranial or caudal migration on lateral view (sagittal plane error)

– Progression of screw position on serial imaging (pathognomonic for cut-out)

– Loss of intervertebral height suggesting implant subsidence

– Kyphotic deformity at fusion level secondary to screw cut-out

– Widening of the screw track or lucency around the screw

Computed Tomography Findings:

– Screw trajectory assessment on sagittal and coronal reformats

– Relationship of screw tip to spinal canal (distance measurement)

– Vertebral body penetration pattern (medial vs. lateral, superior vs. inferior)

– Bone quality surrounding screw

– Exact screw position relative to neural structures

MRI Findings:

– Screw artifact with signal void

– T2 hyperintensity around malpositioned screw suggesting edema or early bone resorption

– Direct visualization of neural compression from screw migration

– Assessment of disc space integrity and fusion progression

Differential Diagnosis

At the 2-month postoperative presentation, alternative diagnoses required consideration before attributing symptoms to screw cut-out: [12]

1. Recurrent Disc Herniation: New discogenic compression would present with progressive radiculopathy. MRI ruled this out by demonstrating intact interbody cages without disc material herniation.

2. Infection/Epidural Abscess: Postoperative wound infection with abscess formation could cause neural compression. Absence of fever, normal postoperative wound healing, and absence of rim enhancement on MRI made infection unlikely.

3. Hematoma or Seroma: Fluid collections could compress nerve roots. MRI showed no significant fluid collections.

4. Adjacent Segment Degeneration: Though possible, adjacent segment disease typically evolves more slowly (years) and would not explain acute symptom recurrence at 8 weeks.

5. Facet Hypertrophy or Reactive Changes: Progressive facet arthropathy could narrow the neural foramen. However, imaging showed no new facet changes compared to preoperative scans.

The temporal relationship between surgery, interval radiographic deterioration of screw position, correlation between screw location and symptomatic nerve root distribution, and absence of alternative pathology made screw cut-out the definitive diagnosis.

Comparison with Literature

The incidence of pedicle screw malposition in spine surgery ranges from 10% to 40% depending on imaging modality (plain film more permissive than CT) and surgeon experience [6, 13]. Symptomatic cut-out requiring revision surgery occurs in approximately 1-3% of TLIF cases.[4,5] However, this risk is substantially elevated in high BMI populations, with some series reporting incidence approaching 8-12% in severely obese patients [8, 10].

Previous biomechanical studies have demonstrated that screw malposition, particularly medial trajectories, reduces pullout strength by up to 60% compared to optimally positioned screws, explaining the predisposition to failure [14]. Furthermore, loading through malpositioned screws creates stress concentration with peak stresses occurring at the implant-bone interface rather than being distributed throughout the construct, accelerating failure [15].

A meta-analysis by recent literature examining complications of TLIF in obese versus normal-weight patients found that obesity was an independent risk factor for hardware failure (odds ratio 2.7) and revision surgery (odds ratio 3.1), with BMI >40 kg/m² conferring the highest risk [10]. This patient’s BMI of 50.2 placed her in the highest-risk category.

Management Strategies

Conservative Approach Not Indicated:

Given the acute symptomatic neural compression from intra-canal screw migration, conservative management was not appropriate. Continued observation would risk progressive neurological deterioration.

Surgical Revision:

Operative intervention was indicated to relieve neural compression, correct screw malposition, and restore spinal stability. Options included:

1. Screw Removal and Replacement: Remove malpositioned screws and place new screws in optimal trajectories, potentially with intraoperative navigation or imaging enhancement.

2. Screw Augmentation: Cement augmentation of screw holes with polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) or calcium phosphate to improve purchase.

3. Supplemental Fixation: Addition of interspinous devices or cross-linking to reduce stress on problematic screws.

4. Anterior Column Support: Anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) could provide additional anterior load-sharing if substantial anterior listhesis persists.

In this case, surgical revision with screw repositioning/replacement was planned, with careful attention to trajectory optimization, potential CT image-guided navigation, and consideration of cement augmentation for any repositioned screws given the suboptimal bone quality and high BMI.

Prevention of Screw Cut-out in High BMI Patients

Several strategies can minimize screw cut-out risk in this challenging population: [7, 11, 16]

1. Meticulous Preoperative Planning:

– Detailed study of preoperative CT with 3D reconstruction

– Measurement of pedicle dimensions and trajectory angles

– Identification of anatomical variants

2. Intraoperative Imaging Enhancement:

– Biplanar fluoroscopy for real-time screw trajectory verification

– Intraoperative CT with navigation (O-arm, Stealth Station, etc.) provides superior accuracy, particularly in obese patients

– Strict adherence to entry point and trajectory

3. Surgical Technique Optimization:

– Wide soft tissue exposure to restore anatomical landmarks

– Palpation of pedicle boundaries with probe before screw insertion

– Slow, deliberate screw advancement with frequent trajectory verification

– Documentation of screw depth and trajectory

4. Implant Selection:

– Longer screws (up to 50-55 mm) to maximize purchase in larger vertebral bodies

– Consideration of larger-diameter screws (7.5 mm) if pedicles accommodate

– Polyaxial screw heads to allow trajectory correction

5. Augmentation Strategies:

– Calcium sulfate or hydroxyapatite fill of screw tracks

– Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) augmentation in low-quality bone

– Consideration of expansion screws that increase diametrically for greater purchase

6. Postoperative Management:

– Early postoperative CT imaging to identify malposition before symptomatic cut-out occurs

– Strict weight-bearing restrictions and activity modification in early postoperative period

– Weight management counseling; bariatric surgery consideration in selected patients

– Compliance with physiotherapy and bracing protocols

7. Surgeon Experience:

– Adequate case volume and training reduce complication rates

– Specialized spine fellowship training provides superior outcomes

– Learning curve considerations—newer surgeons may benefit from navigation systems more than experienced surgeons

Technical Pearls from This Case

1. Fluoroscopy Limitations: Even with fluoroscopic guidance, this case demonstrates that standard intraoperative imaging can be insufficient in high BMI patients. Navigation or O-arm imaging should be strongly considered as standard of care.

2. Immediate Postoperative Imaging: Early postoperative imaging (CT obtained before discharge or within 48 hours) can identify malposition before symptomatic cut-out occurs, allowing prompt revision.

3. Two-Month Postoperative Imaging: At the 2-month point, serial radiographs should be scrutinized for signs of screw migration. This patient’s imaging changes were evident at this timepoint, allowing intervention before neurological deterioration.

4. BMI Consideration: High BMI should trigger heightened vigilance and potentially lower thresholds for supplemental imaging or navigation techniques.

5. Patient Selection: Severely obese patients (BMI >50) with multiple comorbidities should have detailed informed consent discussions regarding elevated complication risks and realistic expectations.

Conclusion

Screw cut-out and implant failure remain serious complications of spine surgery, with significantly elevated incidence in high BMI populations. This case of a 42-year-old obese female (BMI 50.2 kg/m²) who developed symptomatic screw cut-out with neural compression two months following TLIF for lumbar spondylolisthesis underscores several critical principles:

1. Anatomical precision is paramount, particularly in challenging body habitus where visualization is compromised.

2. Intraoperative imaging technology (navigation, O-arm CT, biplanar fluoroscopy) should be liberally employed in high-risk patients rather than reserved for selected cases.

3. Early postoperative imaging can identify malposition before symptomatic neural compromise occurs, allowing planned revision rather than emergency intervention.

4. High BMI patients require heightened vigilance, modified surgical technique, and potentially different implant strategies to reduce failure risk.

5. Surgeon experience and training significantly influence outcomes, particularly in complex cases.

6. Weight management should be an integral component of perioperative care in obese spine surgery patients.

7. Revision surgery, when necessary, should address not only the immediate problem (repositioning screws) but also underlying factors (bone quality, load-sharing, biomechanics) to prevent recurrent failure.

As spine surgeons increasingly encounter obese and severely obese patients in clinical practice, understanding the unique challenges this population presents and implementing evidence-based preventive strategies is essential for achieving optimal functional outcomes and minimizing the burden of revision surgery.

References

[1] Mobbs RJ, Phan K, Malham G, et al. Lumbar interbody fusion: techniques, indications and comparison of approaches. J Spine Surg. 2015;1(1):2-18. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2414-469X.2015.01.02

[2] Foley KT, Holly LT, Schwender JD. Minimally invasive lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(15S):S26-S35. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.BRS.0000076895.52418.5E

[3] Adogwa O, Parker SL, Bydon A, et al. Comparative effectiveness of transforaminal versus posterolateral lumbar interbody fusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2013;80(3-4):e215-e223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2013.01.040

[4] Liang J, Lieberman I, Raad M, et al. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion: operative technique and safety analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33(12):1418-1426. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e31817156a1

[5] Esses SI, Botsford DJ, Kostuik JP. Evaluation of the patient with failed back surgery syndrome. Instr Course Lect. 1993;42:165-170.

[6] Jang JH, Lee SH, Kim CH, et al. Pedicle screw-related complications in minimally invasive spinal surgery: incidence and prevention. Asian Spine J. 2011;5(3):194-201. https://doi.org/10.4184/asj.2011.5.3.194

[7] Kim HJ, Lee HM, Kim SM, et al. The impact of obesity on postoperative complications and clinical outcomes after lumbar spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(23):1816-1824. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000002238

[8] Marques CD, Melão V, Pessoa OF, et al. Obesity as a risk factor for complications of spine surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Spine J. 2020;10(4):505-516. https://doi.org/10.1177/2192568220908295

[9] Oliveira ML, Hawkins MA, Callahan MJ, et al. Mechanisms linking obesity and adipose tissue inflammation to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15(6):602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-015-0602-y

[10] Patel AA, Spiker WR, Daubs MD, et al. Obesity and spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(20):E1218-E1223. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0000000000000576

[11] Lehman RA Jr, Kuklo TR, Belmont PJ Jr, et al. The effect of pedicle screw fit: a biomechanical study of pedicle screw fixation in a synthetic model of the human lumbar spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(8):770-776. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.BRS.0000049337.27677.2E

[12] Vaccaro AR, Barsa P, Shields CB, et al. Compliance of the spine to direct digitally controlled loading: a technical note. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(4):367-373. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199702150-00003

[13] Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(22):2257-2270. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa070302

[14] Kuklo TR, Bridwell KH, Lewis SJ, et al. Minimum 2-year analysis of sacropelvic fixation and L5-S1 fusion using S1 alar iliac screws and pelvic fixation in adult lumbosacral spondylolisthesis patients ≥50 years of age: a matched-pair analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(20):2144-2150. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e318154b4a4

[15] Coe JD, Warden KE, Herzig DS, et al. Influence of bone mineral density on the fixation of thoracolumbar implants. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15(9):902-907. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199009000-00013

[16] Cho W, Cho SK, Wu C. The assessment of adjacent segment degeneration after lumbar fusion: a comparison between proximal and distal adjacent segments. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(26):E926-E932. https://doi.org/10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b8628e

| How to Cite this article: Vatkar A, Kale S, Shinde S. Screw Cut-out and Implant Failure in High BMI Patient Following TLIF: A Case Report and Technical Considerations. Journal of Orthopaedic Complications. September-December 2025;2(3):33-40. |