Arthritis after Calcaneal Fracture – A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis

Review Article | Vol 2 | Issue 3 | September-December 2025 | page: 12-23 | Abhijit Bandyopadhyay

Submitted Date: 15-02-2025, Review Date: 10-03-2025, Accepted Date: 08-08-2025 & Published Date: 10-12-2025

https://doi.org/10.13107/joc.2025.v02.i03.36

Authors: Abhijit Bandyopadhyay [1]

[1] Department of Orthopeadics, Woodland Multispeciality Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Abhijit Bandyopadhyay,

Department of Orthopeadics, Woodland Multispeciality Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India.

Email: abhi_34358@rediffmail.com

Abstract

Background: Post-traumatic arthritis (PTA) is a common complication of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures, greatly interfering with patient mobility and quality of life. Regardless of numerous treatment methods, there continues to be debate over the best method to reduce the risk of PTA. This systematic review and meta-analysis seek to evaluate the frequency, risk factors, and outcomes of PTA after calcaneal fractures and compare surgical and non-surgical treatments.

Materials and Methods: The systematic literature search was done in the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar databases. The extracted data involved study design, sample size, fracture type, treatment, duration of follow-up, criteria for diagnosis of arthritis, and the primary outcomes. Meta-analysis was carried out using the Review Manager tool.

Results: Fifteen studies involving 1,097 patients were included. Overall, PTA prevalence was significantly disparate depending on treatment modality and fracture severity. Sanders Type III fractures had a 47% risk for subtalar fusion, and Type II fractures had a decreased rate of 19% (P < 0.05). Open reduction and internal fixation had no major long-term functional benefit over minimally invasive methods, which were linked to reduced wound complications and fewer reoperations (P < 0.05). Meta-analysis findings showed high heterogeneity among studies evaluating Visual Analog Scale pain scores (I2 = 99%), suggesting variability in pain relief outcomes. Despite surgical intervention improving pain and alignment, complications remained comparable between treatment approaches (I2 = 22%). Nonoperative treatment was linked to higher PTA rates and poorer functional results in comparison with surgery. Comorbid conditions such as smoking and the severity of the fracture, as well as delayed intervention, were variables linked to higher PTA risk.

Conclusion: PTA is a common issue after calcaneal fractures, with surgical treatment usually resulting in improved long-term results compared with non-surgical treatment. Nevertheless, the preference for surgical methods substantially affects complication rates and function restoration. Future research needs to determine specific standards of protocols depending on fracture severity and patient-specific variables to maximize the outcomes of treatment.

Keywords: Post-traumatic arthritis, Calcaneal fractures, Surgical treatment, Fracture severity, Quality of life.

Introduction

The calcaneus, the largest tarsal bone, possesses four articular surfaces [1, 2]. Fractures of the calcaneus occur most commonly among tarsal fractures, making up 1–2% of all fractures [1, 2]. About 75% of such injuries are of the posterior facet type with intra-articular extension [3]. Such serious lower limb fractures are usually caused by high-energy trauma, for example, falls or motor vehicle crashes, that cause axial loading forces. Their influence on patients’ lives is significant, with health outcomes similar to those for myocardial infarction and chronic renal disease [3].

IACF’s have the main fracture line that splits the posterior facet into medial and lateral fragments. The constant fragment, a superomedial fragment, is fixed to the talus through the deltoid and interosseous talocalcaneal ligaments [4]. There are many classification systems, but the Sanders and Essex-Lopresti classifications are the most applied ones [5]. The Sanders system classifies fractures according to the number of fracture lines on semi-coronal computed tomography at the widest point of the talus: type I (nondisplaced), type II (single fracture line, two-part), type III (three-part with central depression), and type IV (comminuted with four or more articular segments) [6, 7]. The Essex-Lopresti system classifies fractures according to the primary and secondary fracture lines, differentiating joint-depression and tongue-type fractures [4, 8]. Joint-depression fractures have a secondary fracture line passing through the calcaneus body, producing a depressed posterior facet fragment and radiographic signs including a diminished Böhler angle, narrowed Gissane angle, and calcaneal shortening [3]. Less frequent, tongue-type fractures have a secondary fracture line passing posteriorly below the facet to the tuberosity, commonly resulting in posterosuperior displacement by Achilles tendon traction [8]. These fractures carry a risk of posterior heel skin necrosis and should have frequent checks for breakdown or blanching since urgent surgery might be necessary [9-11].

The calcaneus plays a critical role in weight-bearing and gait biomechanics, distributing ground reaction forces upon heel strike, the lateral plantar process (LPP) cooperating with the tuberosity to distribute loads [12]. The structure of the LPP is akin to that of the inferior tuberosity regarding bone volume fraction and anisotropy, but its thinly spaced trabeculae facilitate increased surface area for force transfer [13]. Displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures (DIACF’s) can predispose to advanced degenerative changes, needing fusion of the talocalcaneal joints [12]. Studies indicate that those who initially undergo open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) frequently require fusion within an average of 22.6 months [14]. Functional outcomes are significantly better in patients who first receive ORIF before subtalar fusion compared to those treated nonoperatively [15]. Proper anatomical restoration of hindfoot alignment during initial treatment may enhance long-term outcomes, even if fusion is later required [15].

Post-traumatic arthritis (PTA) is a frequent complication of calcaneal fractures, primarily due to chondrocyte damage and articular surface disruption [16]. Intra-articular fractures significantly reduce chondrocyte viability, with studies reporting an average of 72.8% ± 12.9% in fracture patients compared to 94.8% ± 1.5% in healthy controls [16]. Dysfunctions of the posterior facet of the subtalar joint, particularly with joint gaps larger than 3 mm, significantly influence contact properties and pressure distribution [17]. Moreover, the cell viability of the chondrocytes will decrease as post-injury latency increases [18]. Subtalar joints are especially at risk of developing PTA due to fractures at this joint, with 81% of talar neck injuries covering such cases [19]. Primary cartilage damage at the time of injury may still lead to subtalar arthritis, even with appropriate management [18]. The severity and displacement of the fracture play a key role, as failure to achieve anatomical reduction can result in chronic instability and PTA [18].

Surgical management, especially ORIF, is recommended for patients suffering DIACFs, more commonly in cases concerning the younger more active cohort [19,20]. However, the choice of treatment is determined according to a variety of factors like age, activity level, and general health; conditions such as smoking, diabetes, and peripheral vascular disease put one at higher risk for surgery [20]. Nonoperative management is reserved for less severely displaced and simpler fracture patterns [1]. For improved functional outcomes with better occlusion and less temporomandibular joint pain, ORIF carries with it a higher risk for complications, including temporary facial nerve injury (5%) and condylar resorption (2%). It also confers an increased American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) rating (89.56), where most are classified as excellent to good [21]. Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) was considered, achieving comparable radiological reductions to ORIF but with a lower incidence of soft tissue complications, with an ensuing AOFAS rating of 82.58 [21]. At the same time, the classical conservative treatment of recurrence in 20% of condylar fractures is far less effective in occlusal correction as compared to ORIF [22]. Similarly, diabetes, neuropathy, alcohol use, and psychiatric disorders also increase the risk of needing to perform subtalar arthrodesis after the tibiotalar arthrodesis [23]. In addition, primary immunodeficiency disorders may help in causing septic arthritis of the subtalar joint [24].

A systematic review and meta-analysis are warranted since there is no agreement on the best treatment for minimizing the risk of arthritis after calcaneal fractures. Varied outcomes from studies complicate making a decisive conclusion. Meta-analysis of the evidence will serve to determine incidence, risk factors, and late results of PTA. It offers a balanced consideration to inform decision-making at the clinical level. In this review, we systematically analyze and compare the incidence, risk factors, and prognosis of arthritis after calcaneal fractures and treatment methods to determine the most efficacious method to reduce PTA.

Materials and Methods

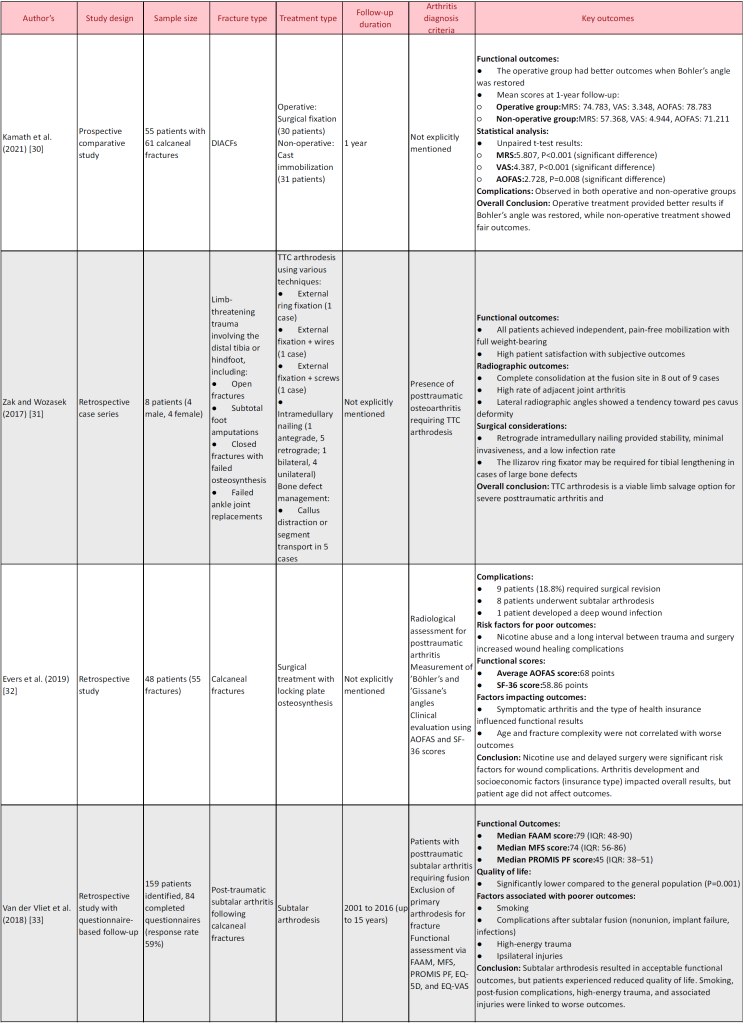

This systematic review and meta-analysis were performed according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses to achieve transparency and replicability. PROSPERO registration of the protocol will be achieved, and the study will conduct a synthesis of evidence regarding the incidence, risk factors, and outcomes of PTA after calcaneal fractures, comparing treatments, including both surgical and non-surgical management. Reviewing randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, case-control studies, and retrospective observational studies measuring long-term functional and radiographic outcomes will be included (Fig. 1).

Search strategy

A systematic literature search was performed utilizing PubMed and Google Scholar for peer-reviewed articles. Search terms will be a combination of both Medical Subject Headings and free-text keywords, using Boolean operators. Keywords like “Calcaneal fracture,” “Post-traumatic arthritis,” “Subtalar arthritis,” “Surgical treatment,” “Non-surgical treatment,” “Open reduction internal fixation,” “Minimally invasive surgery,” “Conservative management,” and “Long-term outcomes” will be employed. The reference lists of included studies and systematic reviews will also be searched manually for additional relevant studies.

Data extraction

Studies were chosen using a two-stage process of screening. Two independent reviewers will first screen titles and abstracts to suggest potentially relevant studies. Full papers will then be screened for eligibility against predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements will be resolved by consultation with a third reviewer.

Inclusion criteria

Studies of PTA after calcaneal fractures, RCTs, cohort studies, case–control studies, and retrospective observational studies, Comparative studies of surgical vs. non-surgical intervention and their influence on the development of arthritis, at least 12-month follow-up to determine long-term outcomes, trials reporting at least one functional, radiographic, or clinical outcome, incidence of PTA and articles published in English were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria

Case reports, conference abstracts, opinions, and editorials, insufficient data studies for outcomes of arthritis, and studies with animal models or cadavers were excluded from the study.

Statistical analysis

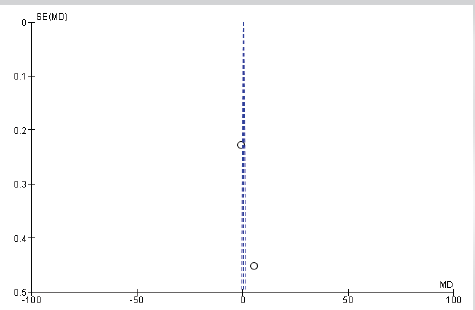

A meta-analysis was carried out using Review Manager software. Heterogeneity was evaluated by ’Cochran’s Q test and the I2 statistic, and a value of I2 >50% will be considered as significant heterogeneity, which would require the use of a random-effects model. Outcomes were visualized in forest plots and funnel plots.

Results

Study selection

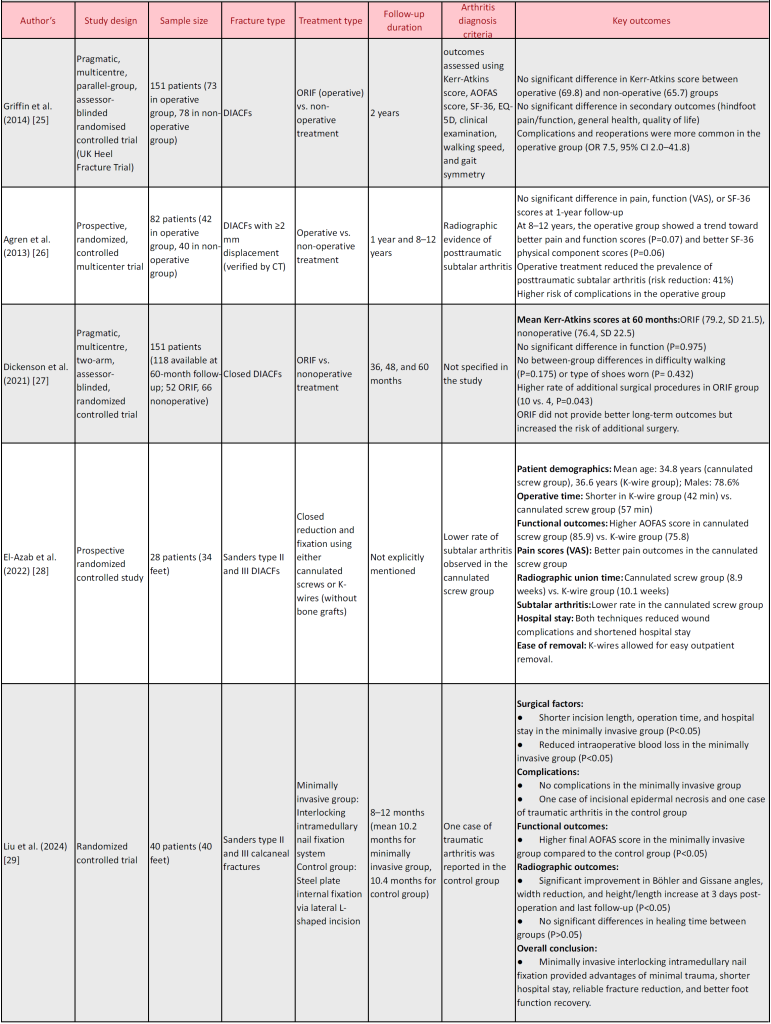

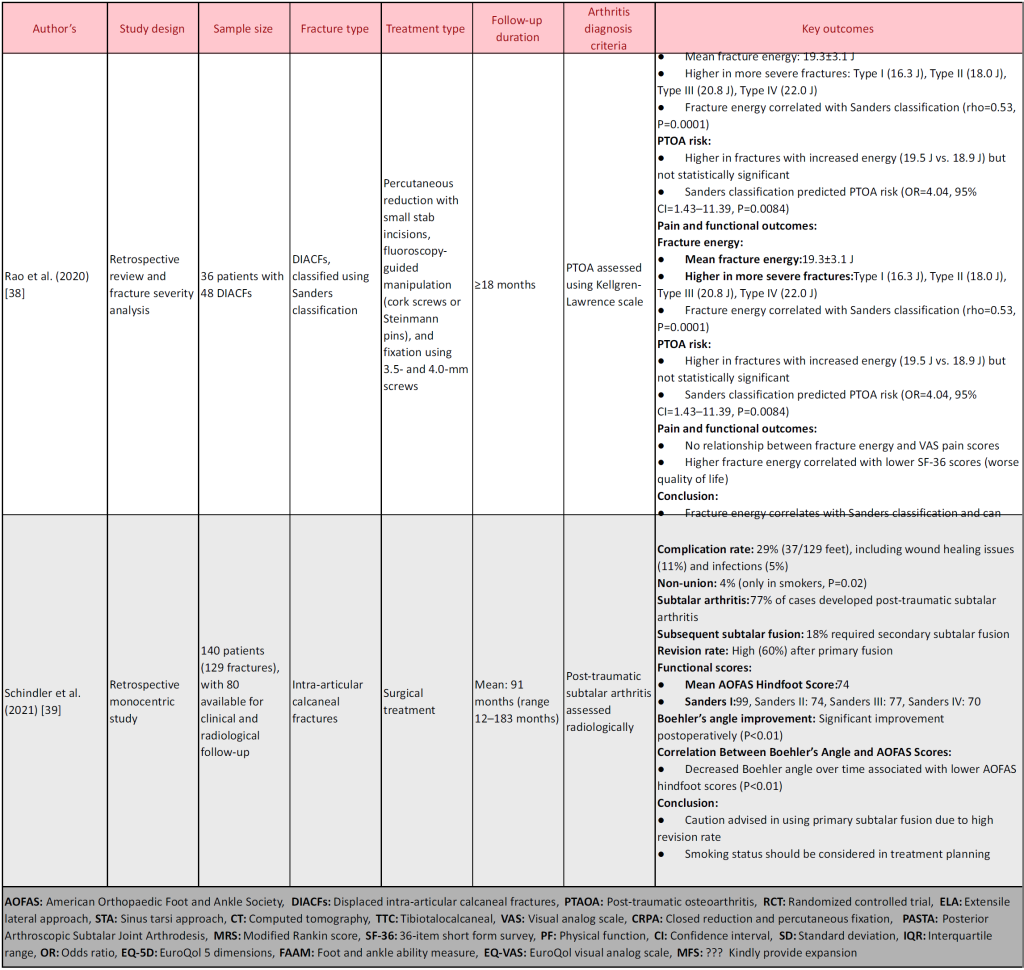

Fifteen studies were selected in this systematic review and meta-analysis after screening and selection according to predefined eligibility criteria. The studies contained RCTs, prospective comparative studies, retrospective analyses, and long-term follow-up to effectively evaluate PTA following DIACF. The studies included in these trials reported an extremely varied sample-to-sample ratio-neatly, ranging from 15 to 159 patients, the follow-up duration extended from 6 months to more than 15 years, and very widely across treatises, ORIF, minimally invasive techniques, and conservative management. The principal outcome considered was the incidence of post-traumatic subtalar arthritis, besides functional recovery, pain scores, radiological outcomes, and complication rates. The following subdivisions summarize the core findings according to some other variables (Table 1).

Incidence of PTA

Some studies documented the incidence of subtalar arthritis after DIACFs. Agren et al. identified 41% fewer cases of PTA in the operative compared to the non-operative group after 8–12 years of follow-up. Schindler et al. documented that 77% of patients developed subtalar arthritis following surgical intervention, with 18% needing subtalar fusion. Dickenson et al. demonstrated no significant difference between ORIF and non-operative care in long-term functional results but increased secondary surgical rates in patients who underwent ORIF. Evers et al. underlined that a higher rate of symptomatic arthritis was found among patients with delayed surgery.

Research on minimally invasive interventions like percutaneous fixation also identified arthritis outcomes. El-Azab et al. discovered a reduced incidence of subtalar arthritis in the group treated with cannulated screw fixation compared to the K-wire group. Likewise, Liu et al. identified fewer complications, improved functional recovery, and less incidence of arthritis among patients receiving interlocking intramedullary nail fixation compared to those receiving steel plate internal fixation.

Comparison of operative versus non-operative treatment outcomes

The UK Heel Fracture Trial (Griffin et al.) reported that ORIF provided no demonstrable symptomatic or functional advantages over non-operative treatment at 2 years. Their results were corroborated by Kamath et al., who showed that restoration of Böhler’s angle was one of the key determinants of functional success following surgery. Van der Vliet et al. confirmed that although the functional results after subtalar fusion were acceptable, patients perceived an impaired quality of life. Conversely, Agren et al. suggested that although ORIF was not associated with immediate benefits within the 1st year, some improvement in pain and function was noted 8–12 years thereafter, together with a lower prevalence of PTA.

Functional outcomes and pain scores

Outcome studies measuring functional recovery employed standardized scoring measures like AOFAS score, Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain, and 36-item short-form survey quality of life scores. Kamath et al. noted significantly superior AOFAS scores in the surgical group (78.8) than the non-surgical group (71.2) in a 1-year follow-up. Similarly, El-Azab et al. reported that patients who were treated with cannulated screws reported improved AOFAS scores (85.9) compared to the K-wire group (75.8). Liu et al. demonstrated that patients who were treated with minimally invasive interlocking intramedullary nail fixation had higher AOFAS scores and improved pain relief (VAS) compared to those treated with steel plate internal fixation. Conversely, Zak and Wozasek (2017) discovered that patients who underwent tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis experienced pain-free mobilization and complete weight-bearing ability, but adjacent joint arthritis was highly prevalent.

Radiological outcomes and fracture healing

The research evaluated radiographic measurements like Böhler’s angle, Gissane’s angle, and calcaneal height/width to measure the quality of fracture reduction and the outcomes of healing. Schindler et al. highlighted that time changes in Böhler’’s angle were associated with poorer functional results (P < 0.01). Equally, Fadle et al. reported improved radiological outcomes in patients who were treated with the sinus tarsi approach (STA), including shorter union time (6.3 weeks compared to 7.1 weeks in the extensile lateral approach group). Rao et al. also associated the severity of fractures with Sanders classification and reported that Type IV (high-energy) fractures had a higher risk of PTA and poorer functional outcomes.

Complications and secondary surgeries

Studies on different techniques of surgery differ in rates of complications. Steelman et al. observed that the infection rate was significantly higher for the ORIF group (24%) than for the CRPF (3%), while the hardware-removal rate was higher in the CRPF (70%) compared to ORIF (31%). Schindler et al. presented a non-union of 4% in smokers only, implicating smoking as a risk factor in any way for poor healing of the bone. Fadle et al. compared injuries to the sinus tarsi and extensile lateral approach (ELA); they found that ELA was associated with many more skin complications (18.9%) and subtalar arthritis (32.6%) compared to STA (3.3% and 9.9%, correspondingly).

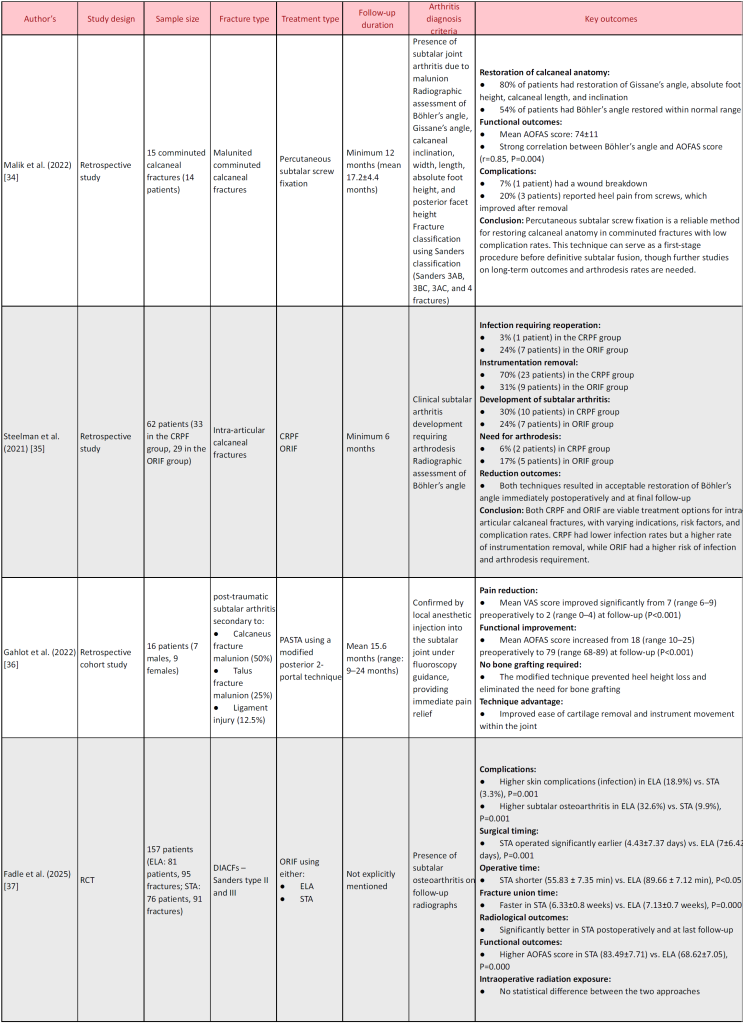

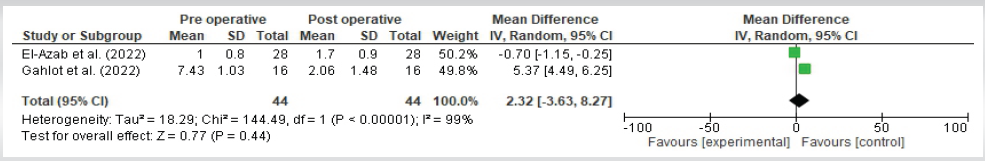

VAS pain score

Two studies reported VAS score, and were eligible for meta-analysis (Fig. 2 and 3). They reported signficant difference in mean VAS score between pre-operative and post-operative (2.23 [95% confidence interval [CI] −3.63–8.27)). Heterogeneity among these studies was high (Tau2 = 18.29; Chi2 = 144.49; df = 5 [P < 0.0001]; I2 = 99%).

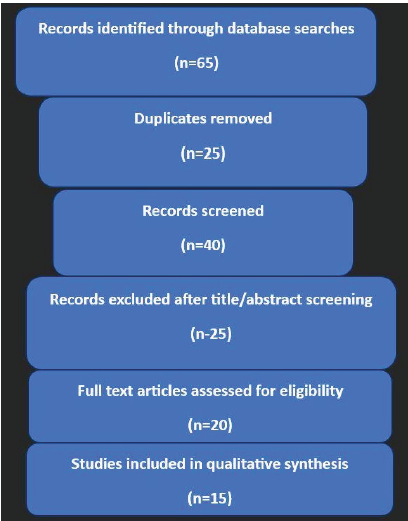

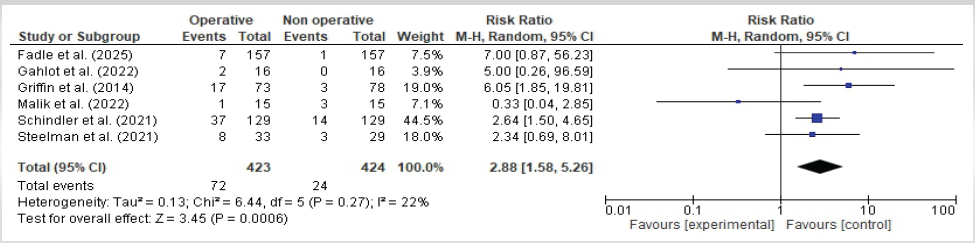

Complications

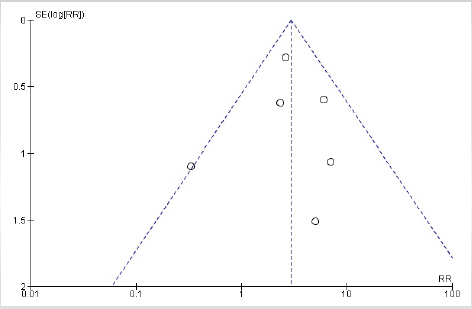

Six studies reported complications, and were eligible for meta-analysis (Fig. 4 and 5). They reported no significant difference in complications between operative and non-operative (relative risk [RR]: 2.88 [95% CI 1.58–5.26]). Heterogeneity among these studies was high (Tau2 = 0.13; Chi2 = 6.44; df = 5 [P = 0.27>0.05]; I2 = 22%).

Discussion

The incident of PTA secondary to calcaneal fractures is one of the graver complications that can impact an individual in the long run. Many factors, some of which are patient-specific, are responsible for the determinative input into the severity of a fracture, hence contributing towards its incidence. Studies have demonstrated many more cases of PTA seen in displaced intra-articular fractures, especially Sanders type III and IV. The extent of joint surface disruption and poor correction of hindfoot alignment largely contribute to the development of PTA in these specific fracture types. Comparative studies done between surgical and conservative interventions reveal that although ORIF greatly restored initial alignment of the fractured surface, it does not always guarantee a long-lasting functional recovery, just as studies by Griffin et al. and Dickenson et al. have reported. Meta-analysis findings also support this, with a significant difference in mean VAS scores between preoperative and postoperative assessments (2.23; 95% CI −3.63–8.27), indicating notable pain relief following surgical intervention. However, heterogeneity among the studies was high (I2 = 99%), suggesting variability in patient responses. Non-operative treatment would likely be safer with a lower risk of complications, but most cases still have residuals like deformity and functionality. Furthermore, minimally invasive techniques, such as percutaneous fixation and interlocking intramedullary nailing, have already shown promise in cutting down PTA risk while also reducing surgical morbidity (Liu et al.; El-Azab et al.). In spite of all the advances in management, many patients still develop subtalar arthritis, occasionally necessitating subsequent surgeries such as subtalar arthrodesis, which ultimately underscores the idea of tailored treatment strategies in relation to fracture features and the uniqueness of each ’patient’s profile.

Calcaneal fractures are among the most common tarsal bone fractures and are constituted by 71.0% of intra-articular fractures [40, 41]. Intra-articular calcaneal fractures usually present a high probability of complications, usually caused by displacement, where 95.0% of intra-articular subtalar calcaneal fractures present displacement [40,41]. The non-operative management results in higher complication rates as compared to those treated surgically [40]. Other than articular collapse and chondrocyte damage, some factors have contributed toward the development of PTA in patients having sustained fractures, with post-fracture cases showing about 72.8% ± 12.9% viability in chondrocytes, which is highly significant when compared to about 94.8% ± 1.5% for controls (P = 0.005) [16]. PTA risk increased with the high-energy-type injuries that correlated with reduced chondrocyte viability (P = 0.13) [16]. In addition, longer injury-to-surgery time lowered the chondrocyte viability further (P = 0.07) [16]. Older age was also associated with lower chondrocyte viability (P = 0.07) [16]. Intra-articular fractures, particularly the displaced type, have an increased chance for complications and can cause subtalar joint PTA by disruption of the joint surface [42].

The comparison between ORIF and minimally invasive reduction with percutaneous fixation (MIRPF) revealed no significant differences in radiological outcomes, although MIRPF demonstrated better functional results and fewer wound complications [43,44]. ORIF was associated with a 30% incidence of wound-healing issues, a longer hospital stay, and extended wound recovery time compared to minimally invasive approaches [43]. Complications of wound healing were associated with nicotine exposure and operative delays [32]. Of those patients treated operatively, 18.8% (9 of 48) needed revision surgery, of which eight received subtalar arthrodesis and one a deep infection in the wound [32]. While hardware problems were not clearly described, evidence of subtalar arthrodesis in more than one instance implies possible malfunction of fixation or poor fracture healing [32,45]. PTA continues to be the most frequent late complication after intra-articular calcaneal fractures [45]. Meta-analysis findings indicate that the overall complication rates between operative and non-operative treatments showed no significant difference (RR: 2.88, 95% CI 1.58–5.26). This suggests that while surgery may provide better fracture alignment and pain relief, the risk of complications remains comparable to non-operative management. Heterogeneity among the studies was low (I2 = 22%), indicating consistent findings across different reports. In conservatively treated fractures, 18% (42 of 233) had severe complications requiring surgical treatment [46]. The best treatment of intra-articular calcaneal fractures is controversial, and conservative measures like elevation, application of ice, early mobilization, and cyclic compression of the plantar arch are used frequently [47].

The Sanders classification system has been widely linked with long-term risk of PTA after DIACFs. Sanders et al. described that Type III fractures had a 47% chance of needing subtalar fusion for arthritis, whereas Type II fractures had a lesser rate of 19%. In addition, Type III fractures were almost four times more likely to require fusion than Type II fractures (RR: 3.94, 95% CI: 1.64–9.48) [48]. Likewise, Rao et al. identified that the Sanders classification was an important predictor of risk for PTA, with odds ratio 4.04 (95% CI: 1.43–11.39, P = 0.0084). Besides, fracture energy correlated well with Sanders classification (rho = 0.53, P = 0.0001), suggesting more severe fractures correspond to greater energy impacts and increased risk of arthritis [38]. Combined articular disruption and fracture energy measurement accurately predicted severity of post-traumatic osteoarthritis in 88% of cases [49]. Even small articular step-offs of 1 mm can change pressure distribution and lead to cartilage degeneration, emphasizing the need for accurate fracture reduction to avoid arthritis risk [50].

We recommend long-term prospective modeling inherent in those studies that seek to understand the complex nature of PTA, following calcaneal fractures, and to identify those factors that may predict long-term outcomes. These very promising modalities include cartilage-sparing techniques and biologic interventions, which could encompass stem cell therapy and regenerative medicine, wherever feasible, toward the aim of joint preservation and procrastination of the onset of arthritis. Otherwise, generalized treatment protocols may be constructed on the basis of fracture patterns, demographics, and disease patterns regarding further optimization of treatment pathways and conditions. Filling in the voids discussed will enable a future for research to inform better clinical decision-making and functional outcomes amid people prone to PTA.

Conclusion

This systematic review emphasizes the significant risk of PTA after calcaneal fractures, especially displaced intra-articular fractures. Surgical methods, such as ORIF and MIS, affect long-term results, with MIS decreasing wound complications. Sanders classification and fracture energy analysis predict the risk of arthritis. Delayed surgery and severity of fracture affect PTA development. Even with progress, there is still a lack of standardized treatment protocols. Future studies will need to investigate long-term analyses, cartilage-sparing strategies, and individually tailored treatment methodologies to reduce risk of PTA, optimize function recovery, and maximize quality of life for patients with calcaneal fractures.

References

1. ’Buckley RE, Tough S. Displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2004;12:172-8.

2. Potter MQ, Nunley JA. Long-term functional outcomes after operative treatment for intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:1854-60.

3. Miller MD, Thompson SR. Miller’s Review of Orthopaedics. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019.

4. Carr JB. Mechanism and pathoanatomy of the intraarticular calcaneal fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993;290:36-40.

5. Rubino R, Valderrabano V, Sutter PM, Regazzoni P. Prognostic value of four classifications of calcaneal fractures. Foot Ankle Int 2009;30:229-38.

6. Sanders R. Intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus: Present state of the art. J Orthop Trauma 1992;6:252-65.

7. Sanders R, Fortin P, DiPasquale T, Walling A. Operative treatment in 120 displaced intraarticular calcaneal fractures. Results using a prognostic computed tomography scan classification. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993;290:87-95.

8. Essex-Lopresti P. The mechanism, reduction technique, and results in fractures of the os calcis, 1951-52. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993;290:3-16.

9. Gardner MJ, Nork SE, Barei DP, Kramer PA, Sangeorzan BJ, Benirschke SK. Secondary soft tissue compromise in tongue-type calcaneus fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2008;22:439-45.

10. Snoap T, Jaykel M, Williams C, Roberts J. Calcaneus fractures: A possible musculoskeletal emergency. J Emerg Med 2017;52:28-33.

11. Wei N, Zhou Y, Chang W, Zhang Y, Chen W. Displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: Classification and treatment. Orthopedics 2017;40:e921-9.

12. Yu JS, Vitellas KM. The calcaneus: Applications of magnetic resonance imaging. Foot Ankle Int 1996;17:771-80.

13. Koneru MC, Harper CM. Comparing lateral plantar process trabecular structure to other regions of the human calcaneus. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2024;307:3152-65.

14. Radnay CS, Clare MP, Sanders RW. Subtalar fusion after displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: Does initial operative treatment matter? J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:541-6.

15. Rammelt S, Sangeorzan BJ, Swords MP. Calcaneal fractures – should we or should we not operate? Indian J Orthop 2018;52:220-30.

16. Ball ST, Jadin K, Allen RT, Schwartz AK, Sah RL, Brage ME. Chondrocyte viability after intra-articular calcaneal fractures in humans. Foot Ankle Int 2007;28:665-8.

17. Barrick B, Joyce DA, Werner FW, Iannolo M. Effect of calcaneus fracture gap without step-off on stress distribution across the subtalar joint. Foot Ankle Int 2017;38:298-303.

18. Rammelt S, Bartoníček J, Park KH. Traumatic injury to the subtalar joint. Foot Ankle Clin 2018;23:353-74.

19. Shamrock AG, Byerly DW. Talar neck fractures. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk542315 [Last accessed on 2024 Jan 03].

20. Sharr PJ, Mangupli MM, Winson IG, Buckley RE. Current management options for displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: Non-operative, ORIF, minimally invasive reduction and fixation or primary ORIF and subtalar arthrodesis. A contemporary review. Foot Ankle Surg 2016;22:1-8.

21. Madadian MA, Simon S, Messiha A. Changing trends in the management of condylar fractures. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2020;58:1145-50.

22. Khurana A, Dhillon MS, Prabhakar S, John R. Outcome evaluation of minimally invasive surgery versus extensile lateral approach in management of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: A randomised control trial. Foot (Edinb) 2017;31:23-30.

23. Chang SH, Hagemeijer NC, Saengsin J, Kusema E, Morris BL, DiGiovanni CW, et al. Short-term risk factors for subtalar arthrodesis after primary tibiotalar arthrodesis. J Foot Ankle Surg 2023;62:68-74.

24. Wynes J, Harris W 4th, Hadfield RA, Malay DS. Subtalar joint septic arthritis in a patient with hypogammaglobulinemia. J Foot Ankle Surg 2013;52:242-8.

25. Griffin D, Parsons N, Shaw E, Kulikov Y, Hutchinson C, Thorogood M, et al. Operative versus non-operative treatment for closed, displaced, intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2014;349:g4483.

26. Agren PH, Wretenberg P, Sayed-Noor AS. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: A prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:1351-7.

27. Dickenson EJ, Parsons N, Griffin DR. Open reduction and internal fixation versus nonoperative treatment for closed, displaced, intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus: Long-term follow-up from the HeFT randomized controlled trial. Bone Joint J 2021;103-B:1040-6.

28. El-Azab H, Ahmed KF, Khalefa AH, Marzouk AR. A prospective comparative study between percutaneous cannulated screws and kirschner wires in treatment of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. Int Orthop 2022;46:2667-83.

29. Liu B, Ma L, Liu C, Zhang B, Wu G. [A prospective study on treatment of sanders type Ⅱ and Ⅲ calcaneal fractures with interlocking intramedullary nail fixation system]. Zhongguo Xiu Fu Chong Jian Wai Ke Za Zhi 2024;38:303-8.

30. Kamath KR, Mallya S, Hegde A. A comparative study of operative and conservative treatment of intraarticular displaced calcaneal fractures. Sci Rep 2021;11:3946.

31. Zak L, Wozasek GE. Tibio-talo-calcaneal fusion after limb salvage procedures-A retrospective study. Injury 2017;48:1684-8.

32. Evers J, Oberste M, Wähnert D, Grüneweller N, Wieskötter B, Milstrey A, et al. Outcome nach operativer therapie von kalkaneus frakturen [Outcome after surgical treatment of calcaneal fractures]. Unfallchirurg 2019;122:778-83.

33. Van Der Vliet QM, Hietbrink F, Casari F, Leenen LP, Heng M. Factors influencing functional outcomes of subtalar fusion for posttraumatic arthritis after calcaneal fracture. Foot Ankle Int 2018;39:1062-9.

34. Malik C, Najefi AA, Patel A, Vris A, Malagelada F, Parker L, et al. Percutaneous subtalar joint screw fixation of comminuted calcaneal fractures: A salvage procedure. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2022;48:4043-51.

35. Steelman K, Bolz N, Feria-Arias E, Meehan R. Evaluation of patient outcomes after operative treatment of intra-articular calcaneus fractures. SICOT J 2021;7:65.

36. Gahlot N, Kunal K, Elhence A. Modified posterior 2-portal technique of arthroscopic subtalar joint arthrodesis: Improved pain and functional outcome at mean 15 months follow-up-a case series. Indian J Orthop 2022;56:1978-84.

37. Fadle AA, Khalifa AA, Shehata PM, El-Adly W, Osman AE. Extensible lateral approach versus sinus tarsi approach for sanders type II and III calcaneal fractures osteosynthesis: A randomized controlled trial of 186 fractures. J Orthop Surg Res 2025;20:8.

38. Rao K, Dibbern K, Day M, Glass N, Marsh JL, Anderson DD. Correlation of fracture energy with sanders classification and post-traumatic osteoarthritis following displaced intra-articular calcaneus fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2019;33:261-6.

39. Schindler C, Schirm A, Zdravkovic V, Potocnik P, Jost B, Toepfer A. Outcomes of intra-articular calcaneal fractures: Surgical treatment of 114 consecutive cases at a maximum care trauma center. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2021;22:234.

40. Bahari Kashani M, Kachooei AR, Ebrahimi H, Peivandi MT, Amelfarzad S, Bekhradianpoor N, et al. Comparative study of peroneal tenosynovitis as the complication of intraarticular calcaneal fracture in surgically and non-surgically treated patients. Iran Red Crescent Med J 2013;15:e11378.

41. Vosoughi AR, Borazjani R, Ghasemi N, Fathi S, Mashhadiagha A, Hoveidaei AH. Different types and epidemiological patterns of calcaneal fractures based on reviewing CT images of 957 fractures. Foot Ankle Surg 2022;28:88-92.

42. Jackson JB 3rd, Jacobson L, Banerjee R, Nickisch F. Distraction subtalar arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Clin 2015;20:335-51.

43. Sampath Kumar V, Marimuthu K, Subramani S, Sharma V, Bera J, Kotwal P. Prospective randomized trial comparing open reduction and internal fixation with minimally invasive reduction and percutaneous fixation in managing displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. Int Orthop 2014;38:2505-12.

44. Amani A, Shakeri V, Kamali A. Comparison of calcaneus joint internal and external fractures in open surgery and minimal invasive methods in patients. Eur J Transl Myol 2018;28:7352.

45. Probe R. In situ subtalar arthrodesis for posttraumatic arthritis of the calcaneus. J Orthop Trauma 2016;30:S45-6.

46. Howard JL, Buckley R, McCormack R, Pate G, Leighton R, Petrie D, et al. Complications following management of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures: A prospective randomized trial comparing open reduction internal fixation with nonoperative management. J Orthop Trauma 2003;17:241-9.

47. Bajammal S, Tornetta P 3rd, Sanders D, Bhandari M. Displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2005;19:360-4.

48. Sanders R, Vaupel ZM, Erdogan M, Downes K. Operative treatment of displaced intraarticular calcaneal fractures: Long-term (10-20 Years) results in 108 fractures using a prognostic CT classification. J Orthop Trauma 2014;28:551-63.

49. Thomas TP, Anderson DD, Mosqueda TV, Van Hofwegen CJ, Hillis SL, Marsh JL, et al. Objective CT-based metrics of articular fracture severity to assess risk for posttraumatic osteoarthritis. J Orthop Trauma 2010;24:764-9.

50. Trumble T, Verheyden J. Remodeling of articular defects in an animal model. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004;423:59-63.

| How to Cite this article: Bandyopadhyay A. Arthritis After Calcaneal Fracture- A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. Journal of Orthopaedic Complications. September-December 2025;2(3):12-23. |